Results & Analysis

Here, we discuss the results of our experiments as described in the

previous section.

Testing the Effect of QiD on Task Performance

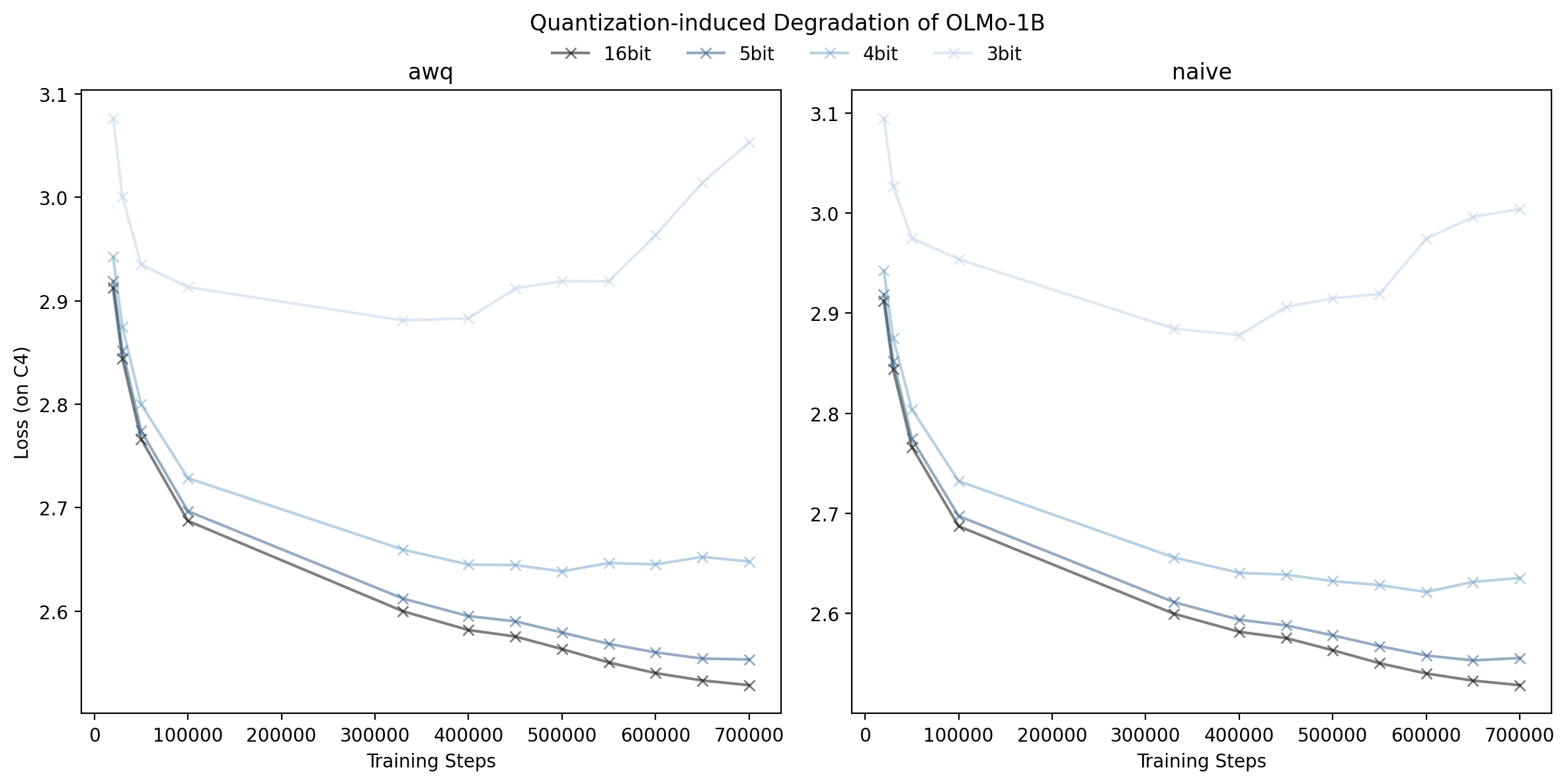

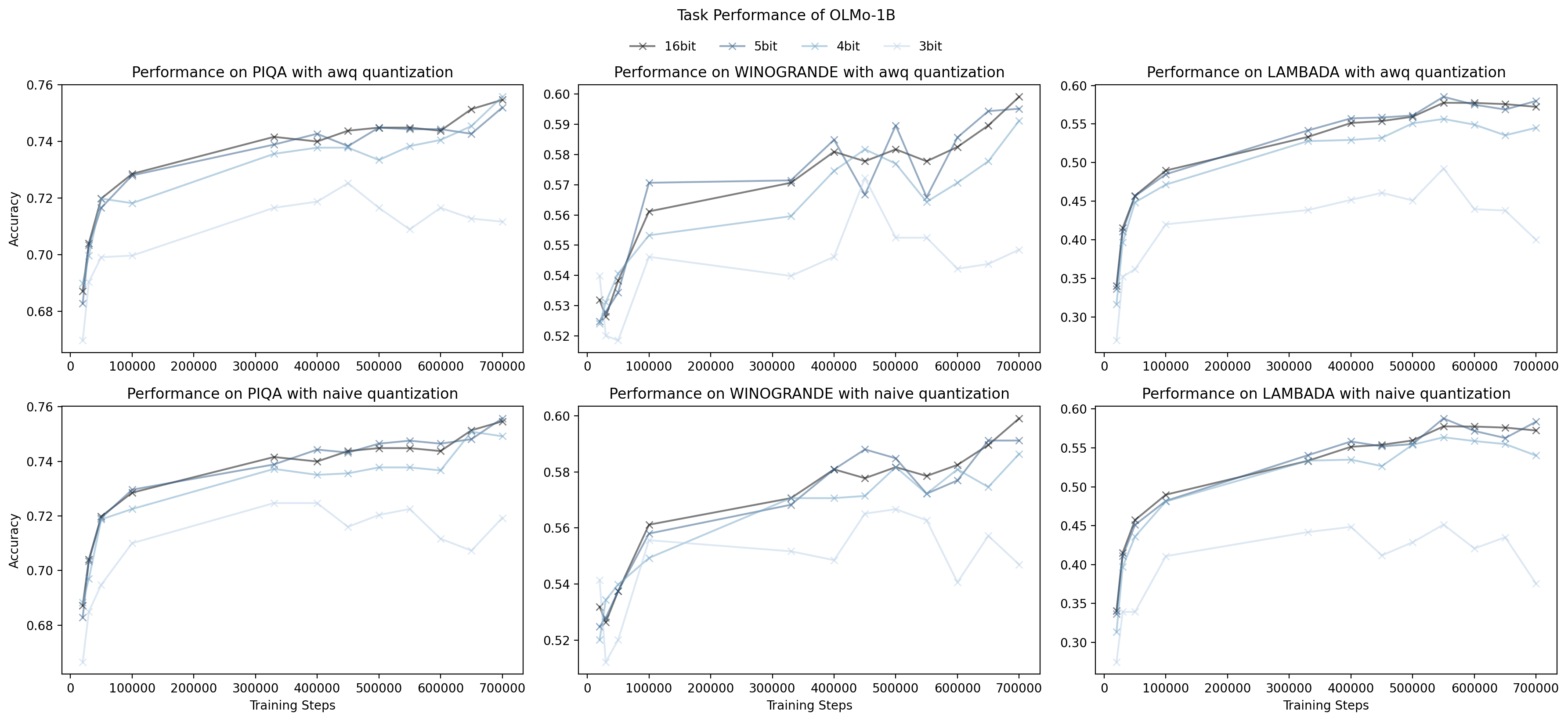

Examining Figure 2, we see that 3 bit quantization has a strong

degradation in task performance for all three datasets, irrespective of

the quantization method. However, we do notice that for 4 and 5 bit

quantization, both naive and AWQ are able to match or nearly match the

performance of full precision across OLMo's training steps, even when

loss is not similar due to QiD. This is an interesting finding and shows

that QiD will not be universal for all things that the model does, and

it suggests that more research is needed into what QiD is doing to the

model and what it impacts.

This also suggests that language modelling loss may not be a perfect

measurement for diagnosing practices that are good and bad for LLMs:

what we care about is task performance, and loss here may be leading us

astray.

Testing the Impact of Activations on QiD

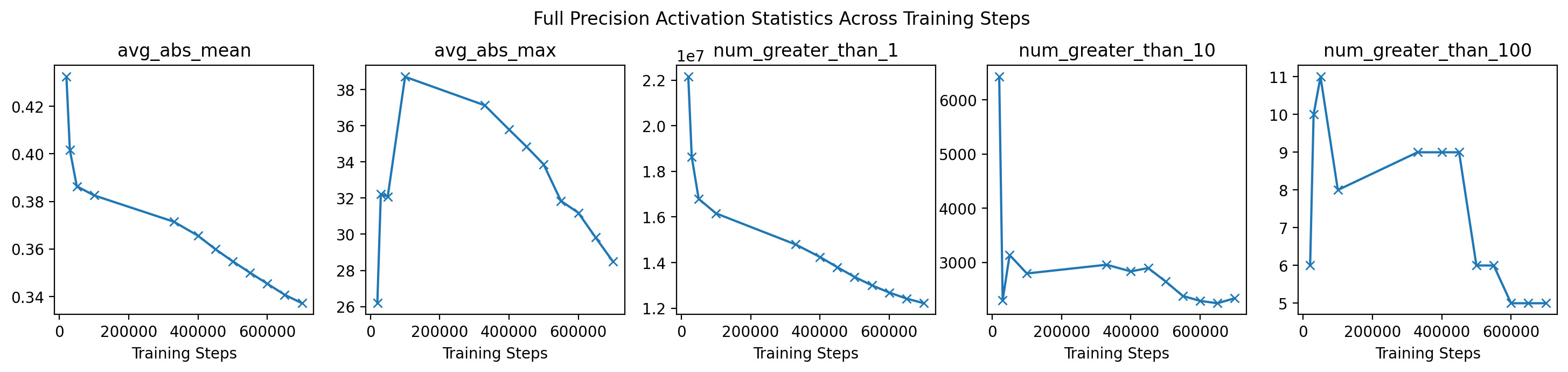

When examining the statistics that we measured from the activations

across training steps, we actually observe the reverse to what we

expected: the size of activations appears to be going down across

training steps, not up. This holds especcially well for the average

absolute mean of the activations and the raw number of activations above

1. Activations may not be the culprit of QiD.

When examining the difference between naive quantization and AWQ, we

find something similar to above: naive quantization and AWQ have very

little difference between both their loss(Figure 1) and task

performance(Figure 2). This further suggests that activations are

unlikely to be causing QiD since naive quantization performs as well as

AWQ.

Because of these two, we have strong reasons to believe that activations

are unlikely to be the cause of QiD.

Testing what Model Component is Causing QiD

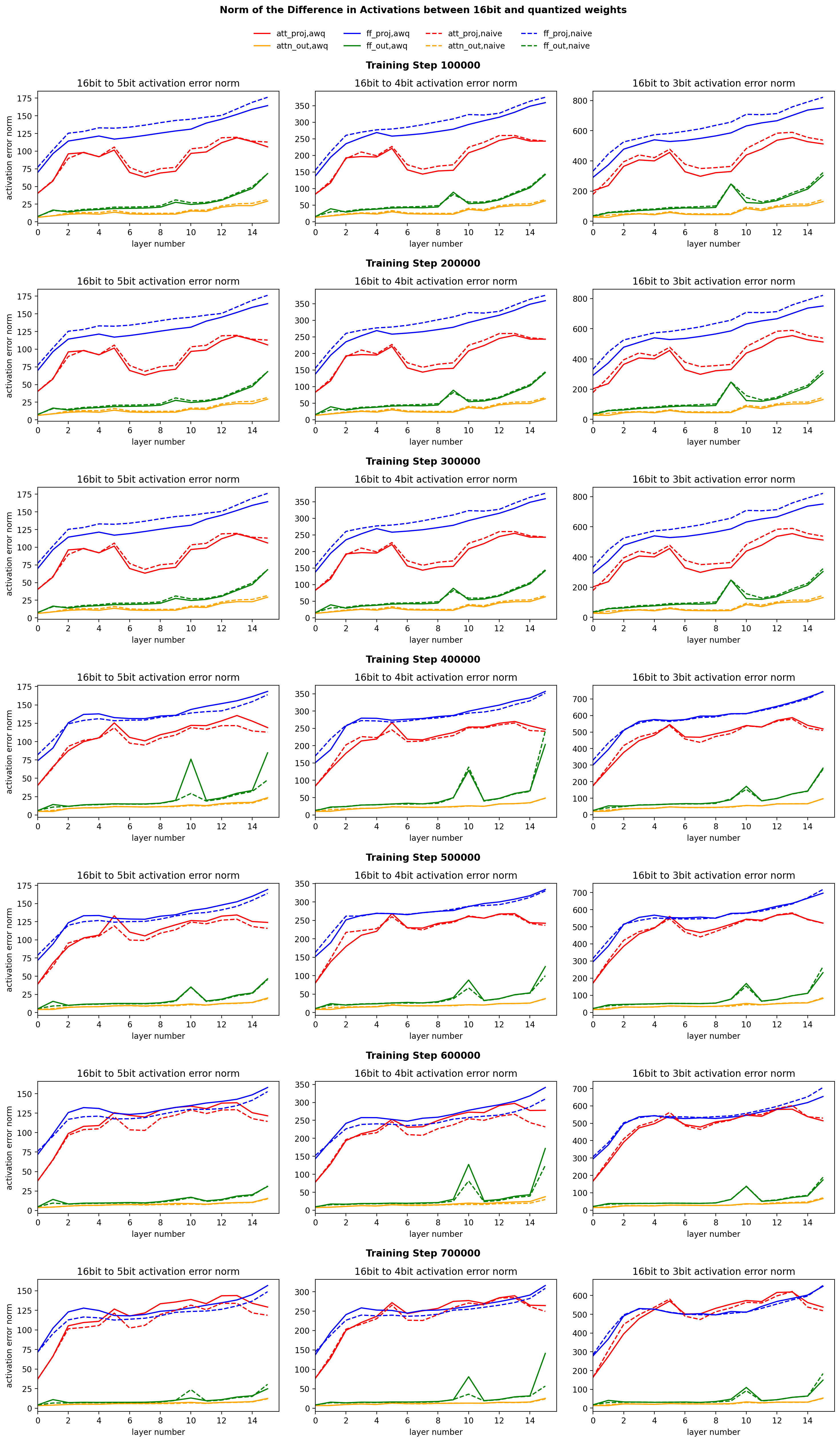

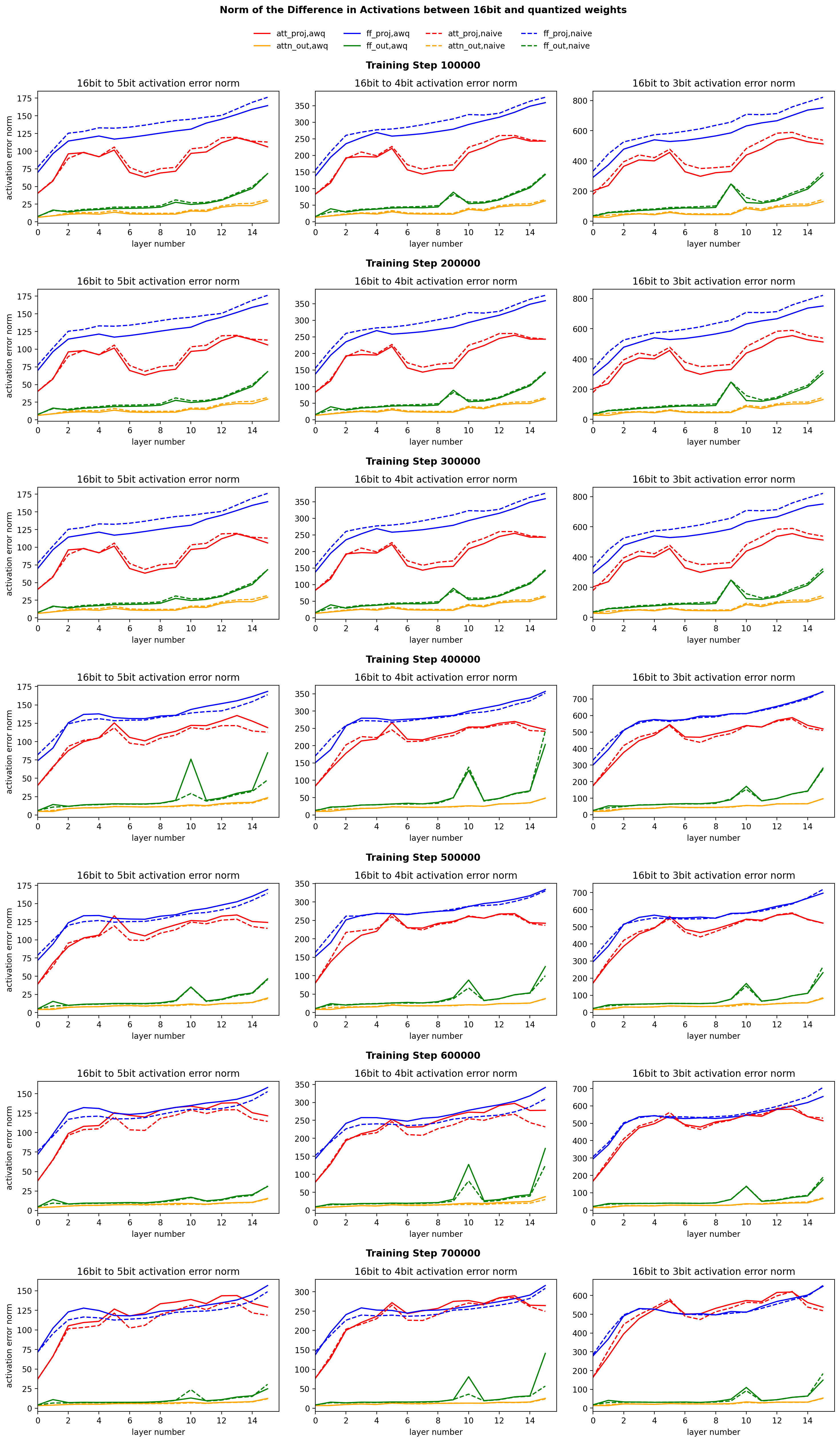

Studying the plot for Figure 4, we look for patterns that are different

across training steps, since as training occurs QiD gets worse. Across

training steps and quantization levels, the norm of the activation error

appears to be pretty similar for the attention output, feed forward

projection, and feed forward output layers, regardless of the

quantization technique used. However, We can notice that across training

steps, the norm of the activation error of the attention projection

module clearly grows across training steps. This finding is independent

of quantization technique and the number of bit used for quantization.

This is a

very interesting finding. This suggests that

the attention projection module is responsible for QiD while the

other three modules appear to not have a notable change in activation

error across training steps.

This finding suggests several remedies for future work. Could keeping

the attention projection layer in higher precision, lets say 8bit, while

keeping the other layers in low precision help allieviate QiD?

Figure 4: We measure the norm of the difference between the full

precision and quantized activations for each layer number and type. We

consider this the activation quantization error. We see that across

training steps, the loss of the attention output, feed forward

projection, and feed forward output layers have similar error. However,

the attention projection layer (red line) has error that grows across

training steps. This finding holds across different quantization levels.

This suggests that the attention projection layer is reponsible for QiD.